When Did Christians Start Using Images of the Crucifixion in Their Art?

Crucifixions and crucifixes have appeared in the arts and popular civilization from earlier the era of the pagan Roman Empire. The crucifixion of Jesus has been depicted in religious art since the 4th century CE. In more modern times, crucifixion has appeared in film and television as well as in fine art, and depictions of other historical crucifixions take appeared as well equally the crucifixion of Christ. Mod art and civilisation have also seen the ascent of images of crucifixion being used to make statements unconnected with Christian iconography, or even just used for stupor value.

Fine art [edit]

Late Antiquity [edit]

The earliest known creative representations of crucifixion predate the Christian era, including Greek representations of mythical crucifixions inspired by the apply of the punishment by the Persians.[1]

The Alexamenos graffito, an early depiction of crucifixion (left), and a mod-day tracing (right)

The Alexamenos graffito, currently in the museum in the Palatine Loma, Rome, is a Roman graffito from the second century CE which depicts a man worshiping a crucified ass. This graffito, though apparently meant equally an insult,[2] is the earliest known pictorial representation of the crucifixion of Jesus.[2] [iii] [4] [5] [6] The text scrawled around the epitome reads Αλεξαμενος ϲεβετε θεον, which approximately translates to "Alexamenos worships God".[seven] [eight] [9] [10]

In the first three centuries of Early Christian fine art, the crucifixion was rarely depicted. Some engraved gems thought to exist 2nd or 3rd century have survived, but the subject does not appear in the art of the Catacombs of Rome, and information technology is thought that at this period the image was restricted to heretical groups of Christians. The primeval Western images clearly originating in the mainstream of the church are 5th-century, including the scene on the doors of Santa Sabina, Rome.[11] Constantine I forbade crucifixion as a method of execution, and early church building leaders regarded crucifixion with horror, and thus, as an unfit subject for artistic portrayal.[12]

The purported discovery of the True Cantankerous by Constantine'due south mother, Helena, and the development of Golgotha as a site for pilgrimage, together with the dispersal of fragments of the relic across the Christian world, led to a change of attitude. Information technology was probably in Syria Palaestina that the image adult, and many of the primeval depictions are on the Monza ampullae, modest metal flasks for holy oil, that were pilgrim's souvenirs from the Holy Land, too equally 5th-century ivory reliefs from Italy.[13] Prior to the Middle Ages, early on Christians preferred to focus on the "triumphant" Christ, rather than a dying one, because the concept of the risen Christ was so key to their faith.[fourteen] The plain cross became depicted, frequently equally a "glorified" symbol, as the crux gemmata, covered with jewels, as many real early medieval processional crosses in goldsmith work were.

Eastern church [edit]

Early on depictions showed a living Christ, and tended to minimize the appearance of suffering, then every bit to draw attention to the positive message of resurrection and faith, rather than to the physical realities of execution.[12] [15] In the early history of the church building in Ireland, important events were often commemorated by erecting pillars with elaborate crucifixes carved into them, such equally where Saint Patrick, returning as a missionary bishop, saw the identify he was held captive in his youth.[sixteen]

Early Byzantine depictions such as that in the Rabbula Gospels often show Christ flanked by Longinus and Stephaton with their spear and pole with vinegar. According to the gospels, the vinegar was offered just before Christ died, and the lance used just after, and then the presence of the two flanking figures symbolizes the "double reality of God and man in Christ".[17] In images from subsequently the end of the Byzantine Iconoclasm, Christ is shown every bit dead, but his "body is undamaged and there is no expression of hurting"; the Eastern church held that Christ's trunk was invulnerable. The "South"-shaped slumped trunk blazon was adult in the 11th century. These images were 1 of the complaints against Constantinople given by Rome in the Great Schism of 1054, although the Gero Cross in Cologne is probably almost a century older.[18]

Western church [edit]

The primeval Western images of a dead Christ may be in the Utrecht Psalter, probably before 835.[19] Other early Western examples include the Gero Cross and the opposite of the Cross of Lothair, both from the end of the tenth century. The first of these is the earliest almost life-size sculpted cross to survive, and in its large calibration represents "suffering in its extreme physical consequences", a tendency that was to continue in the West.[20] Such figures, especially as roods, large painted or sculpted crucifixes hung loftier in front of the chancel of churches, became very important in Western art, providing a sharp contrast with Eastern Orthodox traditions, where the field of study was never depicted in monumental sculpture, and increasingly rarely even in small Byzantine ivories. By contrast, an altar cross, almost ever a crucifix, became compulsory in Western churches in the Middle Ages,[21] and small wall-mounted crucifixes were increasingly pop in Catholic homes from the Counter-Reformation, if not earlier.

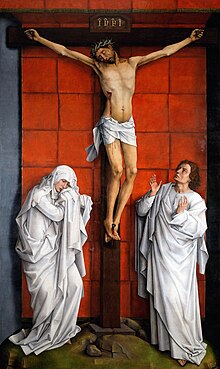

As a broad generalization, the earliest depictions, before about 900, tended to prove all three crosses (those of Jesus, the Good Thief and the Bad Thief), but later medieval depictions mostly showed merely Jesus and his cross. From the Renaissance either blazon might be shown. The number of other figures shown depended on the size and medium of the work, merely there was a similar trend for early depictions to evidence a number of figures, giving manner in the High Middle Ages to just the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist, shown standing on either side of the cantankerous, as in the Stabat Mater depictions, or sculpted or painted on panels at the finish of each arm of a rood cross.

The soldiers were less likely to be shown, but others of the party with Mary and John might be. Angels were often shown in the heaven, and the Hand of God in some early depictions gave way to a pocket-size figure of God the Father in the heavens in some later ones, those these were always in the minority. Other elements that might be included were the sun and moon (evoking the concealment of the heavens at the moment of Christ's death), and Ecclesia and Synagoga. Although according to the Gospel accounts his wear was removed from Jesus before his crucifixion, most artists have thought it proper to represent his lower body as draped in some way. In i type of sculpted crucifix, of which the Volto Santo in Lucca is the classic example, Christ continued to vesture the long collobium robe of the Rabbula Gospels.

A crowded Gothic narrative treatment, workshop of Giotto, c. 1330

In the Gothic menses more elaborate narrative depictions developed, including many extra figures of Mary Magdalene, disciples, specially The Three Marys behind the Virgin Mary, soldiers often including an officer on a horse, and angels in the sky. The moment when Longinus the centurion pierces Christ with his spear (the "Holy Lance") is often shown, and the blood and water spurting from Christ's side is often caught in a beaker held by an angel. In larger images the other two crosses might render, but most frequently not. In some works donor portraits were included in the scene.[22] Such depictions begin in the late twelfth century, and become mutual where space allows in the 13th century.[23]

Related scenes such equally the Deposition of Christ, Entombment of Christ and Nailing of Christ to the Cross developed. In the Tardily Middle Ages, increasingly intense and realistic representations of suffering were shown,[24] reflecting the development of highly emotional andachtsbilder subjects and devotional trends such as German mysticism; some, like the Throne of Mercy, Man of Sorrows and Pietà, related to the Crucifixion. The aforementioned trend afflicted the delineation of other figures, notably in the "Swoon of the Virgin", who is very usually shown fainting in paintings of between 1300 and 1500, though this depiction was attacked past theologians in the 16th century, and became unusual. Later on typically more than tranquil depictions during the Italian Renaissance—though not its Northern equivalent, which produced works such equally the Isenheim Altarpiece—there was a render to intense emotionalism in the Bizarre, in works such every bit Peter Paul Rubens's Elevation of the Cross.

The scene always formed part of a cycle of images of the Life of Christ later on most 600 (though it is noticeably absent before) and usually in one of the Life of the Virgin; the presence of Saint John made it a mutual subject for altarpieces in churches dedicated to him. From the belatedly Middle Ages diverse new contexts for images were devised, from such big scale monuments as the "calvaire" of Brittany and the Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy to the thousands of small wayside shrines found in many parts of Catholic Europe, and the Stations of the Cross in the majority of Cosmic churches.

-

14th-century wood crucifix, Milan

-

18th-century Russian Orthodox brass crucifix

-

-

-

Modern fine art [edit]

Crucifixion has appeared repeatedly as a theme in many forms of modernistic art.

The surrealist Salvador Dalí painted Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), representing the cross equally a hypercube. Fiona Macdonald describes the 1954 painting equally showing a classical pose of Christ superimposed on a mathematical representation of the time that is both unseeable and spiritual;[26] Gary Bolyer assesses information technology equally "one of the most beautiful works of the mod era."[27] The sculpture Construction (Crucifixion): Homage to Mondrian, by Barbara Hepworth, stands on the grounds of Winchester Cathedral. Porfirio DiDonna's abstruse Crucifixion is one of a number of religious works he painted in the 1960s, "blending the artist'due south devotion to the liturgy and his commitment to painting".[28] The "Welsh Window", given to the 16th Street Baptist Church after information technology was bombed by four Ku Klux Klansmen in 1963, is a work of back up and solidarity. The stained glass window depicts a blackness man, artillery outstretched, reminiscent of the crucifixion of Jesus; it was sculpted by John Petts, who also initiated a entrada in Wales to heighten money to help rebuild the church building.[29]

Lensman Robert Mapplethorpe's 1975 self-portrait shows the artist, nude and smiling, posed as if crucified.[30] [31] The 1983 painting Crucifixion, by Nabil Kanso, employs a perspective that places the viewer backside Christ's cross. In 1987 lensman Andres Serrano created Piss Christ, a controversial photo that shows a small plastic crucifix submerged in a drinking glass of the creative person'southward urine, in which Serrano intended to describe sympathetically the abuse of Jesus by his executioners.[32] In the 1990s, Marcus Reichert painted a serial of crucifixions, though he did not identify the figure as Christ, merely as a representation of human suffering.[33]

Other artists have used crucifixion imagery as a class of protestation. In 1974, Chris Burden had himself crucified to a Volkswagen in Trans-Stock-still. Robert Cenedella painted a crucified Santa Claus every bit a protest against Christmas commercialization,[34] displayed in the window of New York's Art Students League in December 1997. In Baronial 2000, performance creative person Sebastian Horsley had himself crucified without the use of whatever analgesics.[35]

-

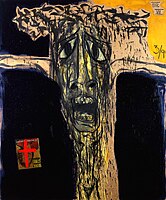

Marcus Reichert, Crucifixion VII (1991), oil and charcoal on linen with newsprint collage, 74" x 62"

-

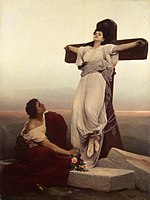

Gabriel von Max's 1866 painting Martyress depicts a crucified young adult female and a immature human laying flowers at her feet – a scene not respective to whatever of the female person martyrs attested in formal Christian hagiography.

Popular art [edit]

Crucifixion in popular art, as with modern art, is sometimes used for its shock value. For example, a World War I Liberty bond poster by Fernando Amorsolo depicts a High german soldier nailing an American soldier, his arms outspread, to the trunk of a tree. Crucifixion imagery is also used to make points in political cartoons. An prototype of a skinhead beingness crucified is a pop symbol among the skinhead subculture, and it is used to convey a sense of societal breach or persecution against the subculture.[36]

-

Postcard protesting German occupation of Poland. Sergey Solomko, circa 1915–17

-

A crucified skinhead, an identifying symbol of the skinhead subculture

Graphic novels [edit]

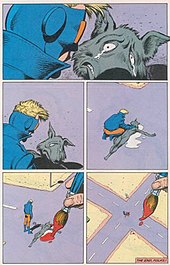

Crucifixion figures prominently in graphic novels from many cultures throughout the globe.[37] In Western comic books, characters in cruciform are seen more frequently than actual crucifixions.[38] For example, Animal Man's fifth result earned an Eisner Laurels nomination in 1989[39] for its "The Coyote Gospel", the story of Crafty, a thinly-disguised Wile E. Coyote (of the Route Runner cartoons)[40] and the depiction at the culmination of the issue of his dead body in cruciform. Superman, often seen as a Christ effigy,[41] has also been crucified, likewise as being shown in cruciform.[42] [43]

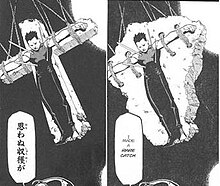

Comparison of images from the manga Fullmetal Alchemist past Hiromu Arakawa, showing crucifixion in the original Japanese version (left), and alteration of the paradigm for distribution in the United States (right)[44]

Crucifixions and crucifixes have appeared repeatedly in Japanese manga and anime.[45] In manga iconography, crucifixes serve 2 purposes: as death symbols, and every bit symbols of justice.[46] Scholars such as Michael Broderick and Susan J. Napier contend that Japanese readers associate crucifixion imagery with apocalyptic themes, and trace this symbolism to Japanese secular views of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, rather than to religious religion.[47] Producers of anime generally deny any religious motivation for depiction of crucifixion.[48] [49] Business concern that Westerners may find these portrayals of crucifixion offensive has led some distributors and localization studios to remove crucifixion imagery from manga such as Fullmetal Alchemist [44] [50] and anime such as Crewman Moon.[51] [52]

Passion plays [edit]

A passion play, Poland, 2006

Passion plays are dramatic presentations of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus. They originated equally expressions of devotion in the Heart Ages. In modern times, critics accept said that some performances are antisemitic.[53]

Movie and television [edit]

Motion-picture show [edit]

Numerous movies have been produced which depict the crucifixion of Jesus. Some of these movies describe the crucifixion in its traditional sectarian form, while others intend to show a more historically accurate account. For example, Ben-Hur (1959), was probably the first motion picture to describe the nails being driven through Jesus' wrists, rather than his palms. Mel Gibson's controversial The Passion of the Christ (2004) depicted an extreme level of violence, but showed the nails being driven into Jesus' palms, equally is traditional, with ropes supporting the wrists.

Although crucifixion imagery is mutual, few films depict actual crucifixion exterior of a Christian context. Spartacus (1960) depicts the mass crucifixions of rebellious slaves along the Appian Manner later the 3rd Servile War. The character Big Bob is crucified by cannibals in Wes Chicken's horror exploitation film The Hills Have Optics (1977) every bit well every bit its 2006 remake. Conan the Barbarian (1982) depicts the protagonist being crucified on the Tree of Woe.

The 1979 British comedy moving picture Monty Python'due south Life of Brian ends with a comical sequence in which several of the cast, including Brian, are crucified past the Romans. The moving-picture show ends with them all singing the song "E'er Expect on the Vivid Side of Life". In this sequence, the characters are not nailed to the crosses, but tied at the wrists to the crossbar, and are standing on smaller crosspieces at foot level.

In the 2010 film Legion, one of the diner patrons is found crucified upside downwards and covered with huge boils.

Goggle box [edit]

Faux crucifixions have been performed in professional wrestling. On the December seven, 1998, edition of WWF Mon Night Raw, professional wrestling character The Undertaker crucified Steve Austin.[54] On October 26, 1996, in Extreme Championship Wrestling, Raven, during a feud with The Sandman, instructed his Raven's Nest to excruciate Sandman.[55]

Other telly performers take used crucifixion to make a bespeak. The Australian comedian John Safran had himself crucified in the Philippines equally role of a Good Friday crucifixion ritual for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation prove, John Safran'southward Race Relations (2009).[56] Singer Robbie Williams performed a stunt on an Apr 2006 Easter Sun bear witness shown on the UK tv set channel Channel iv, in which he was affixed to a cross and pierced with needles.[57]

The HBO telly serial Rome (2005–2007) contained several depictions of crucifixion, every bit it was a mutual torture method during the historical catamenia the evidence takes place in.

In the 2010 Starz television series Spartacus: Blood and Sand, Segovax, a slave recruit to the gladiatorial ludus of Lentulus Batiatus, attempts to assassinate Spartacus in the ludus washrooms and is crucified for doing so "afterwards being parted from his erect".

Crucifixion has been depicted in the television series Xena: Warrior Princess (1995–2001), where its depiction has been cited in feminist studies as illustrating trigger-happy and misogynist tendencies within a messianic prototype.[58]

In the History Channel series "Vikings", the character Æthelstan, after being captured by the Saxons and named an backslider, is shown wearing a crown of thorns and being nailed to a cross. After the cross is raised he is taken down at the order of King Ecbert.[ commendation needed ]

The Japanese science fiction series Neon Genesis Evangelion features crucifixion as a recurring motif.

During the Pilot episode of Smallville, Clark Kent was tied up (simply his underwear and a crimson S painted on his chest) on a scarecrow pole, resembling very much similar a cross, and subdued with a Kryptonite necklace.

Video games [edit]

In Danganronpa Another Episode: Ultra Despair Girls, i of the women gets ultimately crucified on a cross with screws as Monokuma plays with the marionette strings.

Music [edit]

Classical music [edit]

Famous depictions of crucifixion in classical music include the St John Passion and St Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach, and Giovanni Battista Pergolesi'due south setting of Stabat Mater. Notable recent settings include the St. Luke Passion (1965) past Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki and the St. John Passion (1982) by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. The 2000 work, La Pasión según San Marcos (St. Mark Passion) by Argentinian Jewish composer Osvaldo Golijov, was named 1 of the meridian classical compositions of the decade[59] for its fusion of traditional passion motifs with Afro-Cuban, tango, Capoeira, and Kaddish themes.[sixty]

Crucifixion has figured prominently in Easter cantatas, oratorios, and requiems. The third section of a full mass, the Credo, contains the following passage at its climax: "Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato, passus et sepultus est," which means "And was crucified likewise for us under Pontius Pilate; he suffered and was cached." This passage was sometimes gear up to music separately as a Crucifixus, the most famous instance being that of Antonio Lotti for 8 voices.

The seven utterances of Jesus while on the Cross, gathered from the 4 gospels, accept inspired many musical compositions, from Heinrich Schütz in 1645 to Ruth Zechlin in 1996, with the all-time known being Joseph Haydn'southward ''composition, written in 1787.

Depictions of crucifixion outside the Christian context are rare. One of the few examples is in Ernest Reyer'south opera Salammbô (1890).

Popular music [edit]

The 1970 stone opera Jesus Christ Superstar by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber ends with Jesus' crucifixion.

The cover art of Tupac Shakur's album The Don Killuminati: The 7 24-hour interval Theory features an image of Tupac being crucified on a cantankerous. He stated that the image was non a mockery of Christ; rather, it showed how he was existence "crucified" past the media.[ citation needed ] Multiple Marilyn Manson videos such as "I Don't Like The Drugs But The Drugs Like Me" and "Blackout White" characteristic crucifixion imagery, oft oddly staged in surreal mod or near modern-mean solar day settings. The Norwegian blackness metal band Gorgoroth had several people on stage affixed to crosses to requite the appearance of crucifixion at a at present infamous concert in Kraków,[61] and repeated this act in the music video for "Etching a Giant." In 2006, vocalist Madonna opened a concert held almost Vatican Urban center with a mock crucifixion, complete with a crown of thorns.[ citation needed ]

Novels [edit]

Sue Monk Kidd'southward 2020 novel The Book of Longings, tells the fictional story of Ana, an educated woman who marries Jesus. D. M. Martin says the novel "reconstructs the crucifixion experience in a fashion more horrible and poignant than whatever of the four Gospels."[62]

See as well [edit]

- Christian symbolism

- Depiction of Jesus

- Descent from the Cross

- Stations of the Cross

- Religious images in Christian theology

Notes [edit]

- ^ Hengel, Martin (1977). Crucifixion in the ancient world and the folly of the message of the cross. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. pp. thirteen and 22. ISBN978-0-8006-1268-9 . Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Viladesau, Richard (1992). The Word in and Out of Season. Paulist Press. p. 46. ISBN978-0-8091-3626-1.

- ^ Walter Lowrie, Monuments of the Early Church, Macmillan, 1901, p. 238

- ^ Dom Dunstan Adams, What is Prayer?, Gracewing Publishing, 1999, p. 48

- ^ Father John J Pasquini, John J. Pasquini, True Christianity: The Catholic Mode, iUniverse, 2003, p. 105

- ^ Augustus John Cuthbert Hare, Walks in Rome, Volume 1, Adamant Media Corporation, 2005, p. 201

- ^ Cosmic Encyclopedia, The Ass (in Extravaganza of Christian Beliefs and Practices)

- ^ The Crucifixion and Docetic Christology Archived July 4, 2008, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ A Sociological Analysis of Graffiti Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charles William Rex, Gnostics and their Remains, 1887, p. 433 note 12

- ^ Schiller, 89–91, fig. 321

- ^ a b Elizabeth A. Dreyer, The Cantankerous in Christian Tradition: From Paul to Bonaventure, Paulist Press, 2001, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Schiller, 89–90, figs. 322–326

- ^ Smith, Julia J. (1 Jan 1984). "Donne and the Crucifixion". The Modernistic Language Review. 79 (iii): 513–525. doi:x.2307/3728859. JSTOR 3728859.

- ^ R. Kevin Seasoltz ,A Sense Of The Sacred: Theological Foundations Of Christian Architecture And Art, 2005, Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 99–110.

- ^ Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba, Penguin books, 1995.

- ^ Schiller, 93

- ^ Schiller, 99 quoted, 94–99

- ^ Schiller, 99 quoted, 94–99, 105–106

- ^ Schiller, 141 quoted, 105–106, 141–142

- ^ That information technology should be a crucifix was first specified in the Roman Missal of 1570

- ^ Schiller, 151–158

- ^ Schiller, 151–152

- ^ Irene Earls, Renaissance Art: A Topical Dictionary, 1987, Greenwood Press, p. 73.

- ^ Rookmaaker, H. R. (1970). Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. Crossway Books. p. 73. ISBN978-0-89107-799-ii.

- ^ Macdonald, Fiona (May eleven, 2016). "The painter who entered the 4th dimension". BBC Civilization.

- ^ Bolyer, Gary (Jan 21, 2013). "Review of Crucifixion Corpus Hypercubus by Salvador Dali". Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Baker, John (2013). Porfirio DiDonna: The Shape of Knowing. Brooklyn, NY: Pressed Wafer. p. 36. ISBN978-i-940396-01-nine.

- ^ Gary Younge. "The Wales Window of Alabama". Produced by Nicola Swords. BBC Radio four.

- ^ "Robert Mapplethorpe, Self Portrait 1975, The Masters' Gallery". cegur.com.

- ^ Murray, Timothy (1993). Like a film: Ideological fantasy on screen, camera and sail. Routlegde. p. 84. ISBN978-0-415-07733-0.

- ^ Heartney, Eleanor (July 1998). "A consecrated critic – contour of popular television art critic Sis Wendy Beckett". Art in America . Retrieved 2010-09-08 .

- ^ Reichert, Marcus; Rozzo, Edward (2007). Fine art and Ego. Foreword by Simon Lane. London: Ziggurat Books. pp. 30–31. ISBN978-0-9546656-5-iv.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ RCenedella Gallery Online Archived 2011-07-fifteen at the Wayback Auto

- ^ The agony and the ecstasy. The Observer, 26 May 2002

- ^ "Crucified Skinhead, Hate Symbols Database". Anti-Defamation League . Retrieved 2019-12-15 .

- ^ Stanley, Sarah (June 2009). "Drawing on God: Theology in Graphic Novels". Theological Librarianship. 2 (i): 83–88. doi:10.31046/tl.v2i1.72.

- ^ Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth pg. 51

- ^ "1989 Volition Eisner Comic Industry Honour". hahnlibrary.net.

- ^ Irvine, Alex (2008), "Animal Human being", in Dougall, Alastair (ed.), The Vertigo Encyclopedia, New York: Dorling Kindersley, p. 27, ISBN978-0-7566-4122-one, OCLC 213309015

- ^ Garrett, Greg (2008). Holy superheroes!: exploring the sacred in comics, graphic novels, and moving picture. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN978-0-664-23191-0 . Retrieved 2011-06-04 .

- ^ "Is the new Superman meant to be Jesus?". BBC News. July 28, 2006. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Batman: Holy Terror, pg. 39

- ^ a b "Viz Edits Fullmetal Alchemist". Anime News Network. September xi, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ Drazen, Patrick (2003). "Organized religion-Based: Christianity, Shinto, and Other Religions in Anime". Anime Explosion! The What? Why? & Wow! Of Japanese Blitheness. Rock Bridge Printing, LLC. pp. 142–154. ISBN978-1-880656-72-3. OCLC 50898281.

- ^ Drazen 2003, p. 149

- ^ Broderick, Michael (2007). "Superflat Eschatology: Renewal and Religion in Anime" (PDF). Animation Studies—Blithe Dialogues: 29–45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-29.

- ^ Navok Rudranath, Jay; Jay Navok, Sushil Grand., Jonathan Mays (2005). Warriors of Legend (2d ed.). North Charleston, South Carolina: Booksurge LLC. pp. 126–27. ISBN 978-1-4196-0814-viii. OCLC 61255404. https://books.google.com/books?id=cQ4PGtPYOugC

- ^ EvaOtaku.com FAQ Kazuya Tsurumaki; see also an interview with Tsurumaki which contains the same quote [i] (Annal link)

- ^ "Viz Responds to 'FMA' Edit". ICv2. September sixteen, 2006. Retrieved April xiv, 2008.

- ^ Drazen 2003, pp. 142–43

- ^ Referring to Western suppression of these images, Patrick Drazen wrote: "It's ironic that a symbol as potent as crucifixion should exist edited out precisely because of that potency. Afterwards all, the style it's more often than not used in anime—when it's used at all—is in a manner Westerners can understand. It becomes a form of torture for someone who doesn't deserve it."(Drazen 2003, pp. 142–43)

- ^ Sennott, Charles Chiliad. "In Poland, new 'Passion' plays on erstwhile hatreds", The Boston Globe, April 10, 2004.

- ^ "Stone Cold gets crucified by Undertaker on Taker's symbol". flickr.com. 2007-09-14.

- ^ "Wrestlinggonewrong.com".

- ^ Philippines villagers bewildered by John Safran comedy stunt

- ^ "Church building Slams Williams Crucifixion Stunt". premiere.com. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ Kennedy, Kathleen (2007). "Xena On The Cross". Feminist Media Studies. 7 (3): 313–332. doi:x.1080/14680770701477966. S2CID 143461262.

- ^ Huizenga, Tom (December 27, 2009). "The Decade In Classical Recordings". NPR. Retrieved April two, 2010.

- ^ "Osvaldo Golijov's Musical "Passion"". wbur.org. April 2, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Jonathan Tisdall. "Norwegian blackness metal band shocks Poland – Aftenposten.no". Aftenposten.no. Archived from the original on 2009-03-09. Retrieved 2009-08-x .

- ^ D.G. Martin (May 27, 2020). "The married woman of Jesus: the Due north Carolina connectedness". Independent Tribune.

References [edit]

- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II,1972 (English translation from High german), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-324-v

External links [edit]

- Age of spirituality : belatedly antiquarian and early Christian art, 3rd to seventh century from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crucifixion_in_the_arts

0 Response to "When Did Christians Start Using Images of the Crucifixion in Their Art?"

Post a Comment